Antimatter isn't immune to gravity, landmark experiment confirms

Antimatter is the mysterious evil twin of matter, but new research proves they do have something fundamental in common

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Thank you for signing up to TheWeek. You will receive a verification email shortly.

There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.

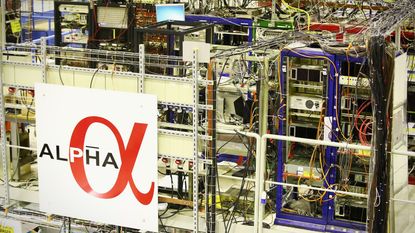

Antimatter — the mysterious substance that's the mirror opposite of matter in most ways — falls downward in gravity like everything else in the universe, a team of physicists reported Wednesday in the journal Nature. In a delicate, groundbreaking experiment conducted at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN), the scientists pretty conclusively proved that antiparticles are not governed by antigravity.

The results are a bit of a wet blanket for science fiction. "The bottom line is that there's no free lunch, and we're not going to be able to levitate using antimatter," study coauthor Joel Fajans of the University of California, Berkeley, told The New York Times. But they are kind of a relief for science. The tug of gravity on antimatter conforms with Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. If the antiparticles had floated upward in the experiment, as some scientists had hypothesized, it would have turned the world of physics on its head.

"Antimatter is just the coolest, most mysterious stuff you can imagine," Jeffrey Hangst, the particle physicist whose 30 years of work trapping antiparticles led to the discovery, told BBC. "As far as we understand, you could build a universe just like ours with you and me made of just antimatter."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For this experiment, Fajans and his colleagues collected and suspended antihydrogen — the antimatter version of hydrogen, with one positively charged electron (positron) orbiting a negatively charged proton (antiproton) — in a magnetic field inside a specially designed tube. When the magnetic force was turned down on the top and bottom of the tube, some of the antiparticles rose but about 80% fell, roughly in line with hydrogen atoms.

The experiment left a bunch of huge questions about antimatter unanswered, however. The big one: Where is it?

When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other in flashes of pure energy. Scientists believe that when the universe was born, the Big Bang created equal quantities of matter and antimatter. And they don't understand why matter won out while antimatter all but disappeared, only fleetingly observed in cosmic ray showers or created by colliding particles in labs like CERN.

One theory to explain what happened posited that all the antimatter was drawn away from the matter by antigravity and formed its own mirror antigravity universe. That hypothesis looks more implausible now.

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Peter Weber is a senior editor at TheWeek.com, and has handled the editorial night shift since the website launched in 2008. A graduate of Northwestern University, Peter has worked at Facts on File and The New York Times Magazine. He speaks Spanish and Italian and plays bass and rhythm cello in an Austin rock band. Follow him on Twitter.

-

Ben Fountain's 6 favorite books about Haiti

Ben Fountain's 6 favorite books about HaitiFeature The award-winning author recommends works by Marie Vieux-Chauvet, Katherine Dunham and more

By The Week Staff Published

-

6 picturesque homes in apartments abroad

6 picturesque homes in apartments abroadFeature Featuring a wall of windows in Costa Rica and a luxury department store-turned-home in New Zealand

By The Week Staff Published

-

Why 2023 has been the year of strikes and labor movements

Why 2023 has been the year of strikes and labor movementsThe Explainer From Hollywood to auto factories, workers are taking to the picket lines

By Justin Klawans Published

-

'Inverse vaccine' shows promise treating MS, other autoimmune diseases

'Inverse vaccine' shows promise treating MS, other autoimmune diseasesNew research effectively cured mice of multiple sclerosis–type symptoms. Could this work in humans?

By Peter Weber Published

-

K2-18b: the exoplanet that could have signs of life

K2-18b: the exoplanet that could have signs of lifeThe Explainer Scientists may have discovered evidence of farts from alien marine creatures 120 light years away

By Arion McNicoll Published

-

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancy

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancySpeed Read Climate change is worsening air quality globally, and there could be deadly consequences

By Devika Rao Published

-

How Antarctica has become the enduring climate change bellwether

How Antarctica has become the enduring climate change bellwetherThe Explainer Despite its remote location, the southernmost continent is stricken with climate change issues

By Justin Klawans Published

-

NASA fully restores contact with Voyager 2 spacecraft

NASA fully restores contact with Voyager 2 spacecraftSpeed Read

By Justin Klawans Published

-

'Extremely dangerous heat wave' to scorch parts of US

'Extremely dangerous heat wave' to scorch parts of USSpeed Read

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Are shark attacks really on the rise?

Are shark attacks really on the rise?The Explainer Reports of shark sightings across U.S. beaches continue to make headlines

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Brain disease linked to head injuries diagnosed in female athlete for first time

Brain disease linked to head injuries diagnosed in female athlete for first timeSpeed Read

By Justin Klawans Published