The pros and cons of the death penalty

Despite global movement towards abolition, public opinion remains divided

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Thank you for signing up to TheWeek. You will receive a verification email shortly.

There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.

The global movement to abolish the death penalty has continued at pace, as capital punishment becomes increasingly viewed as a human-rights issue.

In 1971, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution that, in order to fully guarantee the right to life (under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), the death penalty should be restricted – with a view to abolishing it altogether. In a landmark ruling (Furman v. Georgia) the following year, the US Supreme Court called death sentences a "cruel and unusual" punishment, "capriciously" applied and "incompatible with evolving standards of decency".

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Council of Europe and the EU both list abolition as a condition of membership, and since the 1990s many African countries have been outlawing the punishment. This summer, Ghana became the 29th country on the continent to abolish the death penalty and the 124th globally. Now, executions are most commonly carried out in China, Iran, Egypt and Saudi Arabia (although there is little reliable data for countries such as Afghanistan, North Korea and Syria). But critics warn that the death penalty can be used as a tool of state oppression rather than judicial punishment. Public opinion remains extremely divided, even in countries where it has long been outlawed.

The Week takes a look at some of the arguments.

Pro: public support

Although use of the death penalty is gradually disappearing in the US, in 2021 the Pew Research Center found that more American adults were in favour of it than not. About 60% were in favour for people convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favoured it.

According to a YouGov poll in 2022, 40% of Britons were still in favour of the death penalty, with Conservative voters far more likely to support it (58%), and those aged over 65 more than twice as likely as those aged 18-24.

The last execution in the UK took place in 1964, but there are still calls to reintroduce capital punishment, with supporters arguing that the death penalty would be more cost-effective than feeding and housing an inmate for the whole of a life-without-parole sentence. A new poll for The Spectator also found that 66% of the UK public backed the death penalty as a just punishment for serial baby murderer Lucy Letby.

Con: wrongful execution risk

One of the most "compelling forces" driving worldwide opinions towards the death penalty has been "the increasing recognition of the potential for error in its use", wrote Saul Lehrfreund, co-director of the London-based NGO The Death Penalty Project, in a blog for the University of Oxford. With justice systems prone to error, bias and coercion, wrongful executions are, in fact, "inevitable".

Since 1993, Washington-based non profit organisation The Death Penalty Information Center has been tracking wrongful executions in the US, going back to the Supreme Court ruling in 1972. In a 2021 report, The Innocence Epidemic, it concluded that at least 185 people had been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death since 1972. Nearly 70% of those cases involved "official misconduct by police, prosecutors or other government officials" – more so in cases involving a defendant of colour.

"The death penalty has always been, and continues to be, disproportionately wielded against black people and other people of colour," explained the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, regarding the US. As of 2019, "black and Hispanic people represent 31% of the US population, but 53% of death-row inmates".

Pro: could reduce crime

The "commonest justification" for the death penalty is that it functions as a "unique deterrent" for others, wrote Lehrfreund, based on the reasoning that an executed convict will commit no further crimes.

The penalty of death is "the most important catalyst to limiting the imitation of the worst kinds of crimes – principally, murder", wrote Armstrong Williams for The Hill. "There must be some form to hold murderers accountable and, historically, the death penalty has been the most effective way of doing so."

When the UK first suspended the death penalty, "many hoped that removing violence from the top end of justice would trickle down through society, making us more civilised", wrote Tim Stanley in The Daily Telegraph. "Instead, crime went up, and today, as predators exploit our liberality, a state without the death penalty resembles a lion tamer without a whip."

Con: not a deterrent

The death penalty has "no deterrent effect", said the American Civil Liberties Union. "Claims that each execution deters a certain number of murders have been thoroughly discredited by social science research."

Most murders are committed either in the heat of passion, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or because of mental illness. The few murderers who plan their crimes "intend and expect to avoid punishment altogether by not getting caught".

The Death Penalty Project concluded after a review of multiple studies that capital punishment "does not deter murder to a marginally greater extent than does the threat or application of life imprisonment". In 2021, the Human Rights Council cited studies which showed that some member states that had abolished the death penalty saw their murder rates stay the same, or even decline.

Pro: sense of retribution

Supporters believe that the death penalty provides a sense of retribution for terrible crimes – "an eye for an eye", as expressed in Exodus 21:24 of the Bible.

It is also "often touted as a punishment providing the only way to truly serve justice and offer closure" for friends and family of murder victims, according to a 2007 study. However, "such rhetoric oversimplifies and often misrepresents the experiences and perspectives" of these "co-victims".

Con: extremely expensive

Many supporters of the death penalty argue that it is more cost-effective than feeding and housing an inmate for the whole of a life-without-parole sentence. But in countries with arduous appeals processes and strong human-rights organisations, the death penalty is – counterintuitively – far more expensive than imprisonment for life.

More than a dozen US states found in 2007 that death penalty cases were up to 10 times more expensive than comparable non-death penalty cases. That year, New Jersey became the first state to ban executions for reasons of "time and money", said NBC News.

According to Equal Justice USA, the death penalty in America is "a bloated government program that has bogged down law enforcement, delayed justice for victims' families, and devoured millions of crime-fighting dollars that could save lives and protect the public".

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Harriet Marsden is a writer for The Week, mostly covering UK and global news and politics. Before joining the site, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, specialising in social affairs, gender equality and culture. She worked for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent, and regularly contributed articles to The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, The New Statesman, Tortoise Media and Metro, as well as appearing on BBC Radio London, Times Radio and “Woman’s Hour”. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, London, and was awarded the "journalist-at-large" fellowship by the Local Trust charity in 2021.

-

Ben Fountain's 6 favorite books about Haiti

Ben Fountain's 6 favorite books about HaitiFeature The award-winning author recommends works by Marie Vieux-Chauvet, Katherine Dunham and more

By The Week Staff Published

-

6 picturesque homes in apartments abroad

6 picturesque homes in apartments abroadFeature Featuring a wall of windows in Costa Rica and a luxury department store-turned-home in New Zealand

By The Week Staff Published

-

Why 2023 has been the year of strikes and labor movements

Why 2023 has been the year of strikes and labor movementsThe Explainer From Hollywood to auto factories, workers are taking to the picket lines

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Over 100 decaying bodies found at Colorado funeral home, launching criminal investigation

Over 100 decaying bodies found at Colorado funeral home, launching criminal investigationSpeed Read The funeral home's owner said he was aware of a "problem" on his property

By Justin Klawans Published

-

'Orwellian nightmare’: passport database to be used to catch thieves

'Orwellian nightmare’: passport database to be used to catch thievesTalking Point Policing minister wants to use personal data to crack down on shoplifting crime wave

By Rebekah Evans, The Week UK Published

-

The most famous prison breaks of all time

The most famous prison breaks of all timeThe Explainer Many people have escaped from behind bars over the decades

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Argentinian police arrest biggest online distributor of Nazi propaganda

Argentinian police arrest biggest online distributor of Nazi propagandaSpeed Reads Officials seized hundreds of texts glorifying Adolf Hitler, denying Holocaust and bearing swastikas

By Harriet Marsden Published

-

Hundreds of Ethiopian migrants ‘killed by Saudi border guards’, says human rights group

Hundreds of Ethiopian migrants ‘killed by Saudi border guards’, says human rights groupSpeed Read Human Rights Watch believes if killings were ordered by government it would constitute a crime against humanity

By The Week Staff Published

-

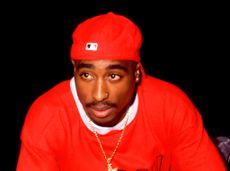

Police reach potential breakthrough in Tupac Shakur murder case

Police reach potential breakthrough in Tupac Shakur murder caseSpeed Read

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Ex-US gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar reportedly stabbed in prison

Ex-US gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar reportedly stabbed in prisonSpeed Read

By Justin Klawans Published

-

Ted Kaczynski, America's infamous 'Unabomber,' dies at 81

Ted Kaczynski, America's infamous 'Unabomber,' dies at 81Speed Read

By Justin Klawans Published